아래의 내용은 위의 링크의 내용을 그대로 복사한 것입니다.

단지 보존의 목적으로만 사용함을 밝힙니다.

With contributions by James Padolsey, Paul Irish, and others. See the GitHub repository for a complete history of contributions.

Copyright © 2010

Licensed by Rebecca Murphey under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 United States license. You are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and remix this work, provided you attribute the work to Rebecca Murphey as the original author and reference the GitHub repository for the work. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar or a compatible license. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to the license.

Table of Contents

- 1. Welcome

- I. JavaScript 101

- II. jQuery: Basic Concepts

- 3. jQuery Basics

- 4. jQuery Core

- 5. Events

- 6. Effects

- 7. Ajax

- 8. Plugins

- III. Advanced Topics

- This Section is a Work in Progress

- 9. Performance Best Practices

- Cache length during loops

- Append new content outside of a loop

- Keep things DRY

- Beware anonymous functions

- Optimize Selectors

- Use Event Delegation

- Detach Elements to Work With Them

- Use Stylesheets for Changing CSS on Many Elements

- Use

$.dataInstead of$.fn.data - Don't Act on Absent Elements

- Variable Definition

- Conditionals

- Don't Treat jQuery as a Black Box

- 10. Code Organization

- 11. Custom Events

List of Examples

- 1.1. An example of inline Javascript

- 1.2. An example of including external JavaScript

- 1.3. Example of an example

- 2.1. A simple variable declaration

- 2.2. Whitespace has no meaning outside of quotation marks

- 2.3. Parentheses indicate precedence

- 2.4. Tabs enhance readability, but have no special meaning

- 2.5. Concatenation

- 2.6. Multiplication and division

- 2.7. Incrementing and decrementing

- 2.8. Addition vs. concatenation

- 2.9. Forcing a string to act as a number

- 2.10. Forcing a string to act as a number (using the unary-plus operator)

- 2.11. Logical AND and OR operators

- 2.12. Comparison operators

- 2.13. Flow control

- 2.14. Values that evaluate to

true - 2.15. Values that evaluate to

false - 2.16. The ternary operator

- 2.17. A switch statement

- 2.18. Loops

- 2.19. A typical

forloop - 2.20. A typical

whileloop - 2.21. A

whileloop with a combined conditional and incrementer - 2.22. A

do-whileloop - 2.23. Stopping a loop

- 2.24. Skipping to the next iteration of a loop

- 2.25. A simple array

- 2.26. Accessing array items by index

- 2.27. Testing the size of an array

- 2.28. Changing the value of an array item

- 2.29. Adding elements to an array

- 2.30. Working with arrays

- 2.31. Creating an "object literal"

- 2.32. Function Declaration

- 2.33. Named Function Expression

- 2.34. A simple function

- 2.35. A function that returns a value

- 2.36. A function that returns another function

- 2.37. A self-executing anonymous function

- 2.38. Passing an anonymous function as an argument

- 2.39. Passing a named function as an argument

- 2.40. Testing the type of various variables

- 2.41. Functions have access to variables defined in the same scope

- 2.42. Code outside the scope in which a variable was defined does not have access to the variable

- 2.43. Variables with the same name can exist in different scopes with different values

- 2.44. Functions can "see" changes in variable values after the function is defined

- 2.45. Scope insanity

- 2.46. How to lock in the value of

i? - 2.47. Locking in the value of

iwith a closure - 3.1. A $(document).ready() block

- 3.2. Shorthand for $(document).ready()

- 3.3. Passing a named function instead of an anonymous function

- 3.4. Selecting elements by ID

- 3.5. Selecting elements by class name

- 3.6. Selecting elements by attribute

- 3.7. Selecting elements by compound CSS selector

- 3.8. Pseudo-selectors

- 3.9. Testing whether a selection contains elements

- 3.10. Storing selections in a variable

- 3.11. Refining selections

- 3.12. Using form-related pseduo-selectors

- 3.13. Chaining

- 3.14. Formatting chained code

- 3.15. Restoring your original selection using

$.fn.end - 3.16. The

$.fn.htmlmethod used as a setter - 3.17. The html method used as a getter

- 3.18. Getting CSS properties

- 3.19. Setting CSS properties

- 3.20. Working with classes

- 3.21. Basic dimensions methods

- 3.22. Setting attributes

- 3.23. Getting attributes

- 3.24. Moving around the DOM using traversal methods

- 3.25. Iterating over a selection

- 3.26. Changing the HTML of an element

- 3.27. Moving elements using different approaches

- 3.28. Making a copy of an element

- 3.29. Creating new elements

- 3.30. Creating a new element with an attribute object

- 3.31. Getting a new element on to the page

- 3.32. Creating and adding an element to the page at the same time

- 3.33. Manipulating a single attribute

- 3.34. Manipulating multiple attributes

- 3.35. Using a function to determine an attribute's new value

- 4.1. Checking the type of an arbitrary value

- 4.2. Storing and retrieving data related to an element

- 4.3. Storing a relationship between elements using

$.fn.data - 4.4. Putting jQuery into no-conflict mode

- 4.5. Using the $ inside a self-executing anonymous function

- 5.1. Event binding using a convenience method

- 5.2. Event biding using the

$.fn.bindmethod - 5.3. Event binding using the

$.fn.bindmethod with data - 5.4. Switching handlers using the

$.fn.onemethod - 5.5. Unbinding all click handlers on a selection

- 5.6. Unbinding a particular click handler

- 5.7. Namespacing events

- 5.8. Preventing a link from being followed

- 5.9. Triggering an event handler the right way

- 5.10. Event delegation using

$.fn.delegate - 5.11. Event delegation using

$.fn.live - 5.12. Unbinding delegated events

- 5.13. The hover helper function

- 5.14. The toggle helper function

- 6.1. A basic use of a built-in effect

- 6.2. Setting the duration of an effect

- 6.3. Augmenting

jQuery.fx.speedswith custom speed definitions - 6.4. Running code when an animation is complete

- 6.5. Run a callback even if there were no elements to animate

- 6.6. Custom effects with

$.fn.animate - 6.7. Per-property easing

- 7.1. Using the core $.ajax method

- 7.2. Using jQuery's Ajax convenience methods

- 7.3. Using

$.fn.loadto populate an element - 7.4. Using

$.fn.loadto populate an element based on a selector - 7.5. Turning form data into a query string

- 7.6. Creating an array of objects containing form data

- 7.7. Using YQL and JSONP

- 7.8. Setting up a loading indicator using Ajax Events

- 8.1. Creating a plugin to add and remove a class on hover

- 8.2. The Mike Alsup jQuery Plugin Development Pattern

- 8.3. A simple, stateful plugin using the jQuery UI widget factory

- 8.4. Passing options to a widget

- 8.5. Setting default options for a widget

- 8.6. Creating widget methods

- 8.7. Calling methods on a plugin instance

- 8.8. Responding when an option is set

- 8.9. Providing callbacks for user extension

- 8.10. Binding to widget events

- 8.11. Adding a destroy method to a widget

- 10.1. An object literal

- 10.2. Using an object literal for a jQuery feature

- 10.3. The module pattern

- 10.4. Using the module pattern for a jQuery feature

- 10.5. Using RequireJS: A simple example

- 10.6. A simple JavaScript file with dependencies

- 10.7. Defining a RequireJS module that has no dependencies

- 10.8. Defining a RequireJS module with dependencies

- 10.9. Defining a RequireJS module that returns a function

- 10.10. A RequireJS build configuration file

jQuery is fast becoming a must-have skill for front-end developers. The purpose of this book is to provide an overview of the jQuery JavaScript library; when you're done with the book, you should be able to complete basic tasks using jQuery, and have a solid basis from which to continue your learning. This book was designed as material to be used in a classroom setting, but you may find it useful for individual study.

This is a hands-on class. We will spend a bit of time covering a concept, and then you’ll have the chance to work on an exercise related to the concept. Some of the exercises may seem trivial; others may be downright daunting. In either case, there is no grade; the goal is simply to get you comfortable working your way through problems you’ll commonly be called upon to solve using jQuery. Example solutions to all of the exercises are included in the sample code.

The code we’ll be using in this book is hosted in a repository on Github. You can download a .zip or .tar file of the code, then uncompress it to use it on your server. If you’re git-inclined, you’re welcome to clone or fork the repository.

JavaScript can be included inline or by including an external file via a script tag. The order in which you include JavaScript is important: dependencies must be included before the script that depends on them.

For the sake of page performance, JavaScript should be included as close to the end of your HTML as is practical. Multiple JavaScript files should be combined for production use.

Methods that can be called on jQuery objects will be referred to as $.fn.methodName. Methods that exist in the jQuery namespace but that cannot be called on jQuery objects will be referred to as$.methodName. If this doesn't mean much to you, don't worry — it should become clearer as you progress through the book.

Remarks will appear like this.

Note

Notes about a topic will appear like this.

In JavaScript, numbers and strings will occasionally behave in ways you might not expect.

The Number constructor, when called as a function (like above) will have the effect of casting its argument into a number. You could also use the unary plus operator, which does the same thing:

Logical operators allow you to evaluate a series of operands using AND and OR operations.

Though it may not be clear from the example, the || operator returns the value of the first truthy operand, or, in cases where neither operand is truthy, it'll return the last of both operands. The &&operator returns the value of the first false operand, or the value of the last operand if both operands are truthy.

Be sure to consult the section called “Truthy and Falsy Things” for more details on which values evaluate to true and which evaluate to false.

Note

You'll sometimes see developers use these logical operators for flow control instead of using if statements. For example:

// do something with foo if foo is truthy foo && doSomething(foo); // set bar to baz if baz is truthy; // otherwise, set it to the return // value of createBar() var bar = baz || createBar();

This style is quite elegant and pleasantly terse; that said, it can be really hard to read, especially for beginners. I bring it up here so you'll recognize it in code you read, but I don't recommend using it until you're extremely comfortable with what it means and how you can expect it to behave.

Sometimes you only want to run a block of code under certain conditions. Flow control — via if andelse blocks — lets you run code only under certain conditions.

Note

While curly braces aren't strictly required around single-line if statements, using them consistently, even when they aren't strictly required, makes for vastly more readable code.

Be mindful not to define functions with the same name multiple times within separate if/elseblocks, as doing so may not have the expected result.

In order to use flow control successfully, it's important to understand which kinds of values are "truthy" and which kinds of values are "falsy." Sometimes, values that seem like they should evaluate one way actually evaluate another.

Sometimes you want to set a variable to a value depending on some condition. You could use anif/else statement, but in many cases the ternary operator is more convenient. [Definition: Theternary operator tests a condition; if the condition is true, it returns a certain value, otherwise it returns a different value.]

While the ternary operator can be used without assigning the return value to a variable, this is generally discouraged.

Rather than using a series of if/else if/else blocks, sometimes it can be useful to use a switch statement instead. [Definition: Switch statements look at the value of a variable or expression, and run different blocks of code depending on the value.]

Switch statements have somewhat fallen out of favor in JavaScript, because often the same behavior can be accomplished by creating an object that has more potential for reuse, testing, etc. For example:

var stuffToDo = {

'bar' : function() {

alert('the value was bar -- yay!');

},

'baz' : function() {

alert('boo baz :(');

},

'default' : function() {

alert('everything else is just ok');

}

};

if (stuffToDo[foo]) {

stuffToDo[foo]();

} else {

stuffToDo['default']();

}We'll look at objects in greater depth later in this chapter.

Loops let you run a block of code a certain number of times.

Note that in Example 2.18, “Loops” even though we use the keyword var before the variable namei, this does not "scope" the variable i to the loop block. We'll discuss scope in depth later in this chapter.

A for loop is made up of four statements and has the following structure:

for ([initialisation]; [conditional]; [iteration]) [loopBody]

The initialisation statement is executed only once, before the loop starts. It gives you an oppurtunity to prepare or declare any variables.

The conditional statement is executed before each iteration, and its return value decides whether or not the loop is to continue. If the conditional statement evaluates to a falsey value then the loop stops.

The iteration statement is executed at the end of each iteration and gives you an oppurtunity to change the state of important variables. Typically, this will involve incrementing or decrementing a counter and thus bringing the loop ever closer to its end.

The loopBody statement is what runs on every iteration. It can contain anything you want. You'll typically have multiple statements that need to be executed and so will wrap them in a block ({...}).

Here's a typical for loop:

A while loop is similar to an if statement, except that its body will keep executing until the condition evaluates to false.

while ([conditional]) [loopBody]

Here's a typical while loop:

You'll notice that we're having to increment the counter within the loop's body. It is possible to combine the conditional and incrementer, like so:

Notice that we're starting at -1 and using the prefix incrementer (++i).

This is almost exactly the same as the while loop, except for the fact that the loop's body is executed at least once before the condition is tested.

do [loopBody] while ([conditional])

Here's a do-while loop:

These types of loops are quite rare since only few situations require a loop that blindly executes at least once. Regardless, it's good to be aware of it.

Usually, a loop's termination will result from the conditional statement not evaluating to true, but it is possible to stop a loop in its tracks from within the loop's body with the break statement.

You may also want to continue the loop without executing more of the loop's body. This is done using the continue statement.

Arrays are zero-indexed lists of values. They are a handy way to store a set of related items of the same type (such as strings), though in reality, an array can include multiple types of items, including other arrays.

While it's possible to change the value of an array item as shown in Example 2.28, “Changing the value of an array item”, it's generally not advised.

Objects contain one or more key-value pairs. The key portion can be any string. The value portion can be any type of value: a number, a string, an array, a function, or even another object.

[Definition: When one of these values is a function, it’s called a method of the object.] Otherwise, they are called properties.

As it turns out, nearly everything in JavaScript is an object — arrays, functions, numbers, even strings — and they all have properties and methods.

Note

When creating object literals, you should note that the key portion of each key-value pair can be written as any valid JavaScript identifier, a string (wrapped in quotes) or a number:

var myObject = {

validIdentifier: 123,

'some string': 456,

99999: 789

};Object literals can be extremely useful for code organization; for more information, read Using Objects to Organize Your Code by Rebecca Murphey.

Functions contain blocks of code that need to be executed repeatedly. Functions can take zero or more arguments, and can optionally return a value.

Functions can be created in a variety of ways:

I prefer the named function expression method of setting a function's name, for some rather in-depth and technical reasons. You are likely to see both methods used in others' JavaScript code.

A common pattern in JavaScript is the self-executing anonymous function. This pattern creates a function expression and then immediately executes the function. This pattern is extremely useful for cases where you want to avoid polluting the global namespace with your code -- no variables declared inside of the function are visible outside of it.

JavaScript offers a way to test the "type" of a variable. However, the result can be confusing -- for example, the type of an Array is "object".

It's common practice to use the typeof operator when trying to determining the type of a specific value.

jQuery offers utility methods to help you determine the type of an arbitrary value. These will be covered later.

"Scope" refers to the variables that are available to a piece of code at a given time. A lack of understanding of scope can lead to frustrating debugging experiences.

When a variable is declared inside of a function using the var keyword, it is only available to code inside of that function -- code outside of that function cannot access the variable. On the other hand, functions defined inside that function will have access to to the declared variable.

Furthermore, variables that are declared inside a function without the var keyword are not local to the function -- JavaScript will traverse the scope chain all the way up to the window scope to find where the variable was previously defined. If the variable wasn't previously defined, it will be defined in the global scope, which can have extremely unexpected consequences;

Closures are an extension of the concept of scope — functions have access to variables that were available in the scope where the function was created. If that’s confusing, don’t worry: closures are generally best understood by example.

In Example 2.44, “Functions can "see" changes in variable values after the function is defined” we saw how functions have access to changing variable values. The same sort of behavior exists with functions defined within loops -- the function "sees" the change in the variable's value even after the function is defined, resulting in all clicks alerting 4.

You cannot safely manipulate a page until the document is “ready.” jQuery detects this state of readiness for you; code included inside $(document).ready() will only run once the page is ready for JavaScript code to execute.

There is a shorthand for $(document).ready() that you will sometimes see; however, I recommend against using it if you are writing code that people who aren't experienced with jQuery may see.

You can also pass a named function to $(document).ready() instead of passing an anonymous function.

The most basic concept of jQuery is to “select some elements and do something with them.” jQuery supports most CSS3 selectors, as well as some non-standard selectors. For a complete selector reference, visit http://api.jquery.com/category/selectors/.

Following are a few examples of common selection techniques.

Note

When you use the :visible and :hidden pseudo-selectors, jQuery tests the actual visibility of the element, not its CSS visibility or display — that is, it looks to see if the element's physical height and width on the page are both greater than zero. However, this test doesn't work with <tr> elements; in this case, jQuery does check the CSS display property, and considers an element hidden if its display property is set to none. Elements that have not been added to the DOM will always be considered hidden, even if the CSS that would affect them would render them visible. (See the Manipulation section later in this chapter to learn how to create and add elements to the DOM.)

For reference, here is the code jQuery uses to determine whether an element is visible or hidden, with comments added for clarity:

jQuery.expr.filters.hidden = function( elem ) {

var width = elem.offsetWidth, height = elem.offsetHeight,

skip = elem.nodeName.toLowerCase() === "tr";

// does the element have 0 height, 0 width,

// and it's not a <tr>?

return width === 0 && height === 0 && !skip ?

// then it must be hidden

true :

// but if it has width and height

// and it's not a <tr>

width > 0 && height > 0 && !skip ?

// then it must be visible

false :

// if we get here, the element has width

// and height, but it's also a <tr>,

// so check its display property to

// decide whether it's hidden

jQuery.curCSS(elem, "display") === "none";

};

jQuery.expr.filters.visible = function( elem ) {

return !jQuery.expr.filters.hidden( elem );

};Once you've made a selection, you'll often want to know whether you have anything to work with. You may be inclined to try something like:

if ($('div.foo')) { ... }This won't work. When you make a selection using $(), an object is always returned, and objects always evaluate to true. Even if your selection doesn't contain any elements, the code inside the ifstatement will still run.

Instead, you need to test the selection's length property, which tells you how many elements were selected. If the answer is 0, the length property will evaluate to false when used as a boolean value.

Every time you make a selection, a lot of code runs, and jQuery doesn't do caching of selections for you. If you've made a selection that you might need to make again, you should save the selection in a variable rather than making the selection repeatedly.

Note

In Example 3.10, “Storing selections in a variable”, the variable name begins with a dollar sign. Unlike in other languages, there's nothing special about the dollar sign in JavaScript -- it's just another character. We use it here to indicate that the variable contains a jQuery object. This practice -- a sort of Hungarian notation -- is merely convention, and is not mandatory.

Once you've stored your selection, you can call jQuery methods on the variable you stored it in just like you would have called them on the original selection.

Note

A selection only fetches the elements that are on the page when you make the selection. If you add elements to the page later, you'll have to repeat the selection or otherwise add them to the selection stored in the variable. Stored selections don't magically update when the DOM changes.

Sometimes you have a selection that contains more than what you're after; in this case, you may want to refine your selection. jQuery offers several methods for zeroing in on exactly what you're after.

jQuery offers several pseudo-selectors that help you find elements in your forms; these are especially helpful because it can be difficult to distinguish between form elements based on their state or type using standard CSS selectors.

- :button

Selects

<button>elements and elements withtype="button"- :checkbox

Selects inputs with

type="checkbox"- :checked

Selects checked inputs

- :disabled

Selects disabled form elements

- :enabled

Selects enabled form elements

- :file

Selects inputs with

type="file"- :image

Selects inputs with

type="image"- :input

Selects

<input>,<textarea>, and<select>elements- :password

Selects inputs with

type="password"- :radio

Selects inputs with

type="radio"- :reset

Selects inputs with

type="reset"- :selected

Selects options that are selected

- :submit

Selects inputs with

type="submit"- :text

Selects inputs with

type="text"

Once you have a selection, you can call methods on the selection. Methods generally come in two different flavors: getters and setters. Getters return a property of the first selected element; setters set a property on all selected elements.

If you call a method on a selection and that method returns a jQuery object, you can continue to call jQuery methods on the object without pausing for a semicolon.

If you are writing a chain that includes several steps, you (and the person who comes after you) may find your code more readable if you break the chain over several lines.

If you change your selection in the midst of a chain, jQuery provides the $.fn.end method to get you back to your original selection.

Note

Chaining is extraordinarily powerful, and it's a feature that many libraries have adapted since it was made popular by jQuery. However, it must be used with care. Extensive chaining can make code extremely difficult to modify or debug. There is no hard-and-fast rule to how long a chain should be -- just know that it is easy to get carried away.

jQuery “overloads” its methods, so the method used to set a value generally has the same name as the method used to get a value. When a method is used to set a value, it is called a setter. When a method is used to get (or read) a value, it is called a getter. Setters affect all elements in a selection; getters get the requested value only for the first element in the selection.

Setters return a jQuery object, allowing you to continue to call jQuery methods on your selection; getters return whatever they were asked to get, meaning you cannot continue to call jQuery methods on the value returned by the getter.

jQuery includes a handy way to get and set CSS properties of elements.

Note

CSS properties that normally include a hyphen need to be camel cased in JavaScript. For example, the CSS property font-size is expressed asfontSize in JavaScript.

Note the style of the argument we use on the second line -- it is an object that contains multiple properties. This is a common way to pass multiple arguments to a function, and many jQuery setter methods accept objects to set mulitple values at once.

As a getter, the $.fn.css method is valuable; however, it should generally be avoided as a setter in production-ready code, because you don't want presentational information in your JavaScript. Instead, write CSS rules for classes that describe the various visual states, and then simply change the class on the element you want to affect.

Classes can also be useful for storing state information about an element, such as indicating that an element is selected.

jQuery offers a variety of methods for obtaining and modifying dimension and position information about an element.

The code in Example 3.21, “Basic dimensions methods” is just a very brief overview of the dimensions functionality in jQuery; for complete details about jQuery dimension methods, visithttp://api.jquery.com/category/dimensions/.

An element's attributes can contain useful information for your application, so it's important to be able to get and set them.

The $.fn.attr method acts as both a getter and a setter. As with the $.fn.css method,$.fn.attr as a setter can accept either a key and a value, or an object containing one or more key/value pairs.

This time, we broke the object up into multiple lines. Remember, whitespace doesn't matter in JavaScript, so you should feel free to use it liberally to make your code more legible! You can use a minification tool later to strip out unnecessary whitespace for production.

Once you have a jQuery selection, you can find other elements using your selection as a starting point.

For complete documentation of jQuery traversal methods, visithttp://api.jquery.com/category/traversing/.

Note

Be cautious with traversing long distances in your documents -- complex traversal makes it imperative that your document's structure remain the same, something that's difficult to guarantee even if you're the one creating the whole application from server to client. One- or two-step traversal is fine, but you generally want to avoid traversals that take you from one container to another.

You can also iterate over a selection using $.fn.each. This method iterates over all of the elements in a selection, and runs a function for each one. The function receives the index of the current element and the DOM element itself as arguments. Inside the function, the DOM element is also available as this by default.

Once you've made a selection, the fun begins. You can change, move, remove, and clone elements. You can also create new elements via a simple syntax.

For complete documentation of jQuery manipulation methods, visithttp://api.jquery.com/category/manipulation/.

There are any number of ways you can change an existing element. Among the most common tasks you'll perform is changing the inner HTML or attribute of an element. jQuery offers simple, cross-browser methods for these sorts of manipulations. You can also get information about elements using many of the same methods in their getter incarnations. We'll see examples of these throughout this section, but specifically, here are a few methods you can use to get and set information about elements.

Note

Changing things about elements is trivial, but remember that the change will affect all elements in the selection, so if you just want to change one element, be sure to specify that in your selection before calling a setter method.

Note

When methods act as getters, they generally only work on the first element in the selection, and they do not return a jQuery object, so you can't chain additional methods to them. One notable exception is $.fn.text; as mentioned below, it gets the text for all elements in the selection.

- $.fn.html

Get or set the html contents.

- $.fn.text

Get or set the text contents; HTML will be stripped.

- $.fn.attr

Get or set the value of the provided attribute.

- $.fn.width

Get or set the width in pixels of the first element in the selection as an integer.

- $.fn.height

Get or set the height in pixels of the first element in the selection as an integer.

- $.fn.position

Get an object with position information for the first element in the selection, relative to its first positioned ancestor. This is a getter only.

- $.fn.val

Get or set the value of form elements.

There are a variety of ways to move elements around the DOM; generally, there are two approaches:

Place the selected element(s) relative to another element

Place an element relative to the selected element(s)

For example, jQuery provides $.fn.insertAfter and $.fn.after. The $.fn.insertAftermethod places the selected element(s) after the element that you provide as an argument; the$.fn.after method places the element provided as an argument after the selected element. Several other methods follow this pattern: $.fn.insertBefore and $.fn.before;$.fn.appendTo and $.fn.append; and $.fn.prependTo and $.fn.prepend.

The method that makes the most sense for you will depend on what elements you already have selected, and whether you will need to store a reference to the elements you're adding to the page. If you need to store a reference, you will always want to take the first approach -- placing the selected elements relative to another element -- as it returns the element(s) you're placing. In this case,$.fn.insertAfter, $.fn.insertBefore, $.fn.appendTo, and $.fn.prependTo will be your tools of choice.

When you use methods such as $.fn.appendTo, you are moving the element; sometimes you want to make a copy of the element instead. In this case, you'll need to use $.fn.clone first.

Note

If you need to copy related data and events, be sure to pass true as an argument to $.fn.clone.

jQuery offers a trivial and elegant way to create new elements using the same $() method you use to make selections.

Note that in the attributes object we included as the second argument, the property name class is quoted, while the property names text and href are not. Property names generally do not need to be quoted unless they are reserved words (as class is in this case).

When you create a new element, it is not immediately added to the page. There are several ways to add an element to the page once it's been created.

Strictly speaking, you don't have to store the created element in a variable -- you could just call the method to add the element to the page directly after the $(). However, most of the time you will want a reference to the element you added, so you don't need to select it later.

You can even create an element as you're adding it to the page, but note that in this case you don't get a reference to the newly created element.

Note

The syntax for adding new elements to the page is so easy, it's tempting to forget that there's a huge performance cost for adding to the DOM repeatedly. If you are adding many elements to the same container, you'll want to concatenate all the html into a single string, and then append that string to the container instead of appending the elements one at a time. You can use an array to gather all the pieces together, then join them into a single string for appending.

var myItems = [], $myList = $('#myList');

for (var i=0; i<100; i++) {

myItems.push('<li>item ' + i + '</li>');

}

$myList.append(myItems.join(''));jQuery offers several utility methods in the $ namespace. These methods are helpful for accomplishing routine programming tasks. Below are examples of a few of the utility methods; for a complete reference on jQuery utility methods, visit http://api.jquery.com/category/utilities/.

- $.trim

Removes leading and trailing whitespace.

$.trim(' lots of extra whitespace '); // returns 'lots of extra whitespace'- $.each

Iterates over arrays and objects.

$.each([ 'foo', 'bar', 'baz' ], function(idx, val) { console.log('element ' + idx + 'is ' + val); }); $.each({ foo : 'bar', baz : 'bim' }, function(k, v) { console.log(k + ' : ' + v); });Note

There is also a method

$.fn.each, which is used for iterating over a selection of elements.- $.inArray

Returns a value's index in an array, or -1 if the value is not in the array.

var myArray = [ 1, 2, 3, 5 ]; if ($.inArray(4, myArray) !== -1) { console.log('found it!'); }- $.extend

Changes the properties of the first object using the properties of subsequent objects.

var firstObject = { foo : 'bar', a : 'b' }; var secondObject = { foo : 'baz' }; var newObject = $.extend(firstObject, secondObject); console.log(firstObject.foo); // 'baz' console.log(newObject.foo); // 'baz'If you don't want to change any of the objects you pass to

$.extend, pass an empty object as the first argument.var firstObject = { foo : 'bar', a : 'b' }; var secondObject = { foo : 'baz' }; var newObject = $.extend({}, firstObject, secondObject); console.log(firstObject.foo); // 'bar' console.log(newObject.foo); // 'baz'- $.proxy

Returns a function that will always run in the provided scope — that is, sets the meaning of

thisinside the passed function to the second argument.var myFunction = function() { console.log(this); }; var myObject = { foo : 'bar' }; myFunction(); // logs window object var myProxyFunction = $.proxy(myFunction, myObject); myProxyFunction(); // logs myObject objectIf you have an object with methods, you can pass the object and the name of a method to return a function that will always run in the scope of the object.

var myObject = { myFn : function() { console.log(this); } }; $('#foo').click(myObject.myFn); // logs DOM element #foo $('#foo').click($.proxy(myObject, 'myFn')); // logs myObject

As mentioned in the "JavaScript basics" section, jQuery offers a few basic utility methods for determining the type of a specific value.

As your work with jQuery progresses, you'll find that there's often data about an element that you want to store with the element. In plain JavaScript, you might do this by adding a property to the DOM element, but you'd have to deal with memory leaks in some browsers. jQuery offers a straightforward way to store data related to an element, and it manages the memory issues for you.

You can store any kind of data on an element, and it's hard to overstate the importance of this when you get into complex application development. For the purposes of this class, we'll mostly use$.fn.data to store references to other elements.

For example, we may want to establish a relationship between a list item and a div that's inside of it. We could establish this relationship every single time we interact with the list item, but a better solution would be to establish the relationship once, and then store a pointer to the div on the list item using $.fn.data:

In addition to passing $.fn.data a single key-value pair to store data, you can also pass an object containing one or more pairs.

Although jQuery eliminates most JavaScript browser quirks, there are still occasions when your code needs to know about the browser environment.

jQuery offers the $.support object, as well as the deprecated $.browser object, for this purpose. For complete documentation on these objects, visit http://api.jquery.com/jQuery.support/ andhttp://api.jquery.com/jQuery.browser/.

The $.support object is dedicated to determining what features a browser supports; it is recommended as a more “future-proof” method of customizing your JavaScript for different browser environments.

The $.browser object was deprecated in favor of the $.support object, but it will not be removed from jQuery anytime soon. It provides direct detection of the browser brand and version.

If you are using another JavaScript library that uses the $ variable, you can run into conflicts with jQuery. In order to avoid these conflicts, you need to put jQuery in no-conflict mode immediately after it is loaded onto the page and before you attempt to use jQuery in your page.

When you put jQuery into no-conflict mode, you have the option of assigning a variable name to replace $.

You can continue to use the standard $ by wrapping your code in a self-executing anonymous function; this is a standard pattern for plugin authoring, where the author cannot know whether another library will have taken over the $.

jQuery provides simple methods for attaching event handlers to selections. When an event occurs, the provided function is executed. Inside the function, this refers to the element that was clicked.

For details on jQuery events, visit http://api.jquery.com/category/events/.

The event handling function can receive an event object. This object can be used to determine the nature of the event, and to prevent the event’s default behavior.

For details on the event object, visit http://api.jquery.com/category/events/event-object/.

jQuery offers convenience methods for most common events, and these are the methods you will see used most often. These methods -- including $.fn.click, $.fn.focus, $.fn.blur,$.fn.change, etc. -- are shorthand for jQuery's $.fn.bind method. The bind method is useful for binding the same hadler function to multiple events, and is also used when you want to provide data to the event hander, or when you are working with custom events.

Sometimes you need a particular handler to run only once -- after that, you may want no handler to run, or you may want a different handler to run. jQuery provides the $.fn.one method for this purpose.

The $.fn.one method is especially useful if you need to do some complicated setup the first time an element is clicked, but not subsequent times.

To disconnect an event handler, you use the $.fn.unbind method and pass in the event type to unbind. If you attached a named function to the event, then you can isolate the unbinding to that named function by passing it as the second argument.

As mentioned in the overview, the event handling function receives an event object, which contains many properties and methods. The event object is most commonly used to prevent the default action of the event via the preventDefault method. However, the event object contains a number of other useful properties and methods, including:

- pageX, pageY

The mouse position at the time the event occurred, relative to the top left of the page.

- type

The type of the event (e.g. "click").

- which

The button or key that was pressed.

- data

Any data that was passed in when the event was bound.

- target

The DOM element that initiated the event.

- preventDefault()

Prevent the default action of the event (e.g. following a link).

- stopPropagation()

Stop the event from bubbling up to other elements.

In addition to the event object, the event handling function also has access to the DOM element that the handler was bound to via the keyword this. To turn the DOM element into a jQuery object that we can use jQuery methods on, we simply do $(this), often following this idiom:

var $this = $(this);

jQuery provides a way to trigger the event handlers bound to an element without any user interaction via the $.fn.trigger method. While this method has its uses, it should not be used simply to call a function that was bound as a click handler. Instead, you should store the function you want to call in a variable, and pass the variable name when you do your binding. Then, you can call the function itself whenever you want, without the need for $.fn.trigger.

You'll frequently use jQuery to add new elements to the page, and when you do, you may need to bind events to those new elements -- events you already bound to similar elements that were on the page originally. Instead of repeating your event binding every time you add elements to the page, you can use event delegation. With event delegation, you bind your event to a container element, and then when the event occurs, you look to see which contained element it occurred on. If this sounds complicated, luckily jQuery makes it easy with its $.fn.live and $.fn.delegate methods.

While most people discover event delegation while dealing with elements added to the page later, it has some performance benefits even if you never add more elements to the page. The time required to bind event handlers to hundreds of individual elements is non-trivial; if you have a large set of elements, you should consider delegating related events to a container element.

Note

The $.fn.live method was introduced in jQuery 1.3, and at that time only certain event types were supported. As of jQuery 1.4.2, the $.fn.delegatemethod is available, and is the preferred method.

jQuery offers two event-related helper functions that save you a few keystrokes.

The $.fn.hover method lets you pass one or two functions to be run when the mouseenter andmouseleave events occur on an element. If you pass one function, it will be run for both events; if you pass two functions, the first will run for mouseenter, and the second will run for mouseleave.

Note

Prior to jQuery 1.4, the $.fn.hover method required two functions.

jQuery makes it trivial to add simple effects to your page. Effects can use the built-in settings, or provide a customized duration. You can also create custom animations of arbitrary CSS properties.

For complete details on jQuery effects, visit http://api.jquery.com/category/effects/.

Frequently used effects are built into jQuery as methods:

- $.fn.show

Show the selected element.

- $.fn.hide

Hide the selected elements.

- $.fn.fadeIn

Animate the opacity of the selected elements to 100%.

- $.fn.fadeOut

Animate the opacity of the selected elements to 0%.

- $.fn.slideDown

Display the selected elements with a vertical sliding motion.

- $.fn.slideUp

Hide the selected elements with a vertical sliding motion.

- $.fn.slideToggle

Show or hide the selected elements with a vertical sliding motion, depending on whether the elements are currently visible.

With the exception of $.fn.show and $.fn.hide, all of the built-in methods are animated over the course of 400ms by default. Changing the duration of an effect is simple.

jQuery has an object at jQuery.fx.speeds that contains the default speed, as well as settings for"slow" and "fast".

speeds: {

slow: 600,

fast: 200,

// Default speed

_default: 400

}It is possible to override or add to this object. For example, you may want to change the default duration of effects, or you may want to create your own effects speed.

Often, you'll want to run some code once an animation is done -- if you run it before the animation is done, it may affect the quality of the animation, or it may remove elements that are part of the animation. [Definition: Callback functions provide a way to register your interest in an event that will happen in the future.] In this case, the event we'll be responding to is the conclusion of the animation. Inside of the callback function, the keyword this refers to the element that the effect was called on; as we did inside of event handler functions, we can turn it into a jQuery object via$(this).

Note that if your selection doesn't return any elements, your callback will never run! You can solve this problem by testing whether your selection returned any elements; if not, you can just run the callback immediately.

jQuery makes it possible to animate arbitrary CSS properties via the $.fn.animate method. The$.fn.animate method lets you animate to a set value, or to a value relative to the current value.

Note

Color-related properties cannot be animated with $.fn.animate using jQuery out of the box. Color animations can easily be accomplished by including the color plugin. We'll discuss using plugins later in the book.

[Definition: Easing describes the manner in which an effect occurs -- whether the rate of change is steady, or varies over the duration of the animation.] jQuery includes only two methods of easing: swing and linear. If you want more natural transitions in your animations, various easing plugins are available.

As of jQuery 1.4, it is possible to do per-property easing when using the $.fn.animate method.

For more details on easing options, see http://api.jquery.com/animate/.

Proper use of Ajax-related jQuery methods requires understanding some key concepts first.

jQuery generally requires some instruction as to the type of data you expect to get back from an Ajax request; in some cases the data type is specified by the method name, and in other cases it is provided as part of a configuration object. There are several options:

- text

For transporting simple strings

- html

For transporting blocks of HTML to be placed on the page

- script

For adding a new script to the page

- json

For transporting JSON-formatted data, which can include strings, arrays, and objects

Note

As of jQuery 1.4, if the JSON data sent by your server isn't properly formatted, the request may fail silently. See http://json.org for details on properly formatting JSON, but as a general rule, use built-in language methods for generating JSON on the server to avoid syntax issues.

- jsonp

For transporting JSON data from another domain

- xml

For transporting data in a custom XML schema

I am a strong proponent of using the JSON format in most cases, as it provides the most flexibility. It is especially useful for sending both HTML and data at the same time.

While jQuery does offer many Ajax-related convenience methods, the core $.ajax method is at the heart of all of them, and understanding it is imperative. We'll review it first, and then touch briefly on the convenience methods.

I generally use the $.ajax method and do not use convenience methods. As you'll see, it offers features that the convenience methods do not, and its syntax is more easily understandable, in my opinion.

jQuery’s core $.ajax method is a powerful and straightforward way of creating Ajax requests. It takes a configuration object that contains all the instructions jQuery requires to complete the request. The $.ajax method is particularly valuable because it offers the ability to specify both success and failure callbacks. Also, its ability to take a configuration object that can be defined separately makes it easier to write reusable code. For complete documentation of the configuration options, visit http://api.jquery.com/jQuery.ajax/.

Note

A note about the dataType setting: if the server sends back data that is in a different format than you specify, your code may fail, and the reason will not always be clear, because the HTTP response code will not show an error. When working with Ajax requests, make sure your server is sending back the data type you're asking for, and verify that the Content-type header is accurate for the data type. For example, for JSON data, the Content-type header should beapplication/json.

There are many, many options for the $.ajax method, which is part of its power. For a complete list of options, visit http://api.jquery.com/jQuery.ajax/; here are several that you will use frequently:

- async

Set to

falseif the request should be sent synchronously. Defaults totrue. Note that if you set this option to false, your request will block execution of other code until the response is received.- cache

Whether to use a cached response if available. Defaults to

truefor all dataTypes except "script" and "jsonp". When set to false, the URL will simply have a cachebusting parameter appended to it.- complete

A callback function to run when the request is complete, regardless of success or failure. The function receives the raw request object and the text status of the request.

- context

The scope in which the callback function(s) should run (i.e. what

thiswill mean inside the callback function(s)). By default,thisinside the callback function(s) refers to the object originally passed to$.ajax.- data

The data to be sent to the server. This can either be an object or a query string, such as

foo=bar&baz=bim.- dataType

The type of data you expect back from the server. By default, jQuery will look at the MIME type of the response if no dataType is specified.

- error

A callback function to run if the request results in an error. The function receives the raw request object and the text status of the request.

- jsonp

The callback name to send in a query string when making a JSONP request. Defaults to "callback".

- success

A callback function to run if the request succeeds. The function receives the response data (converted to a JavaScript object if the dataType was JSON), as well as the text status of the request and the raw request object.

- timeout

The time in milliseconds to wait before considering the request a failure.

- traditional

Set to true to use the param serialization style in use prior to jQuery 1.4. For details, seehttp://api.jquery.com/jQuery.param/.

- type

The type of the request, "POST" or "GET". Defaults to "GET". Other request types, such as "PUT" and "DELETE" can be used, but they may not be supported by all browsers.

- url

The URL for the request.

The url option is the only required property of the $.ajax configuration object; all other properties are optional.

If you don't need the extensive configurability of $.ajax, and you don't care about handling errors, the Ajax convenience functions provided by jQuery can be useful, terse ways to accomplish Ajax requests. These methods are just "wrappers" around the core $.ajax method, and simply pre-set some of the options on the $.ajax method.

The convenience methods provided by jQuery are:

- $.get

Perform a GET request to the provided URL.

- $.post

Perform a POST request to the provided URL.

- $.getScript

Add a script to the page.

- $.getJSON

Perform a GET request, and expect JSON to be returned.

In each case, the methods take the following arguments, in order:

- url

The URL for the request. Required.

- data

The data to be sent to the server. Optional. This can either be an object or a query string, such as

foo=bar&baz=bim.Note

This option is not valid for

$.getScript.- success callback

A callback function to run if the request succeeds. Optional. The function receives the response data (converted to a JavaScript object if the data type was JSON), as well as the text status of the request and the raw request object.

- data type

The type of data you expect back from the server. Optional.

Note

This option is only applicable for methods that don't already specify the data type in their name.

The $.fn.load method is unique among jQuery’s Ajax methods in that it is called on a selection. The $.fn.load method fetches HTML from a URL, and uses the returned HTML to populate the selected element(s). In addition to providing a URL to the method, you can optionally provide a selector; jQuery will fetch only the matching content from the returned HTML.

jQuery’s ajax capabilities can be especially useful when dealing with forms. The jQuery Form Pluginis a well-tested tool for adding Ajax capabilities to forms, and you should generally use it for handling forms with Ajax rather than trying to roll your own solution for anything remotely complex. That said, there are a two jQuery methods you should know that relate to form processing in jQuery:$.fn.serialize and $.fn.serializeArray.

The advent of JSONP -- essentially a consensual cross-site scripting hack -- has opened the door to powerful mashups of content. Many prominent sites provide JSONP services, allowing you access to their content via a predefined API. A particularly great source of JSONP-formatted data is theYahoo! Query Language, which we'll use in the following example to fetch news about cats.

jQuery handles all the complex aspects of JSONP behind-the-scenes -- all we have to do is tell jQuery the name of the JSONP callback parameter specified by YQL ("callback" in this case), and otherwise the whole process looks and feels like a normal Ajax request.

Often, you’ll want to perform an operation whenever an Ajax requests starts or stops, such as showing or hiding a loading indicator. Rather than defining this behavior inside every Ajax request, you can bind Ajax events to elements just like you'd bind other events. For a complete list of Ajax events, visit http://docs.jquery.com/Ajax_Events.

Plugins extend the basic jQuery functionality, and one of the most celebrated aspects of the library is its extensive plugin ecosystem. From table sorting to form validation to autocompletion ... if there’s a need for it, chances are good that someone has written a plugin for it.

The quality of jQuery plugins varies widely. Many plugins are extensively tested and well-maintained, but others are hastily created and then ignored. More than a few fail to follow best practices.

Google is your best initial resource for locating plugins, though the jQuery team is working on an improved plugin repository. Once you’ve identified some options via a Google search, you may want to consult the jQuery mailing list or the #jquery IRC channel to get input from others.

When looking for a plugin to fill a need, do your homework. Ensure that the plugin is well-documented, and look for the author to provide lots of examples of its use. Be wary of plugins that do far more than you need; they can end up adding substantial overhead to your page. For more tips on spotting a subpar plugin, read Signs of a poorly written jQuery plugin by Remy Sharp.

Once you choose a plugin, you’ll need to add it to your page. Download the plugin, unzip it if necessary, place it your application’s directory structure, then include the plugin in your page using a script tag (after you include jQuery).

Sometimes you want to make a piece of functionality available throughout your code; for example, perhaps you want a single method you can call on a jQuery selection that performs a series of operations on the selection. In this case, you may want to write a plugin.

Most plugins are simply methods created in the $.fn namespace. jQuery guarantees that a method called on a jQuery object will be able to access that jQuery object as this inside the method. In return, your plugin needs to guarantee that it returns the same object it received, unless explicitly documented otherwise.

Here is an example of a simple plugin:

For more on plugin development, read Mike Alsup's essential post, A Plugin Development Pattern. In it, he creates a plugin called $.fn.hilight, which provides support for the metadata plugin if it's present, and provides a centralized method for setting global and instance options for the plugin.

Note

This section is based, with permission, on the blog post Building Stateful jQuery Plugins by Scott Gonzalez.

While most existing jQuery plugins are stateless — that is, we call them on an element and that is the extent of our interaction with the plugin — there’s a large set of functionality that doesn’t fit into the basic plugin pattern.

In order to fill this gap, jQuery UI has implemented a more advanced plugin system. The new system manages state, allows multiple functions to be exposed via a single plugin, and provides various extension points. This system is called the widget factory and is exposed asjQuery.widget as part of jQuery UI 1.8; however, it can be used independently of jQuery UI.

To demonstrate the capabilities of the widget factory, we'll build a simple progress bar plugin.

To start, we’ll create a progress bar that just lets us set the progress once. As we can see below, this is done by calling jQuery.widget with two parameters: the name of the plugin to create and an object literal containing functions to support our plugin. When our plugin gets called, it will create a new plugin instance and all functions will be executed within the context of that instance. This is different from a standard jQuery plugin in two important ways. First, the context is an object, not a DOM element. Second, the context is always a single object, never a collection.

The name of the plugin must contain a namespace; in this case we’ve used the nmk namespace. There is a limitation that namespaces be exactly one level deep — that is, we can't use a namespace like nmk.foo. We can also see that the widget factory has provided two properties for us.this.element is a jQuery object containing exactly one element. If our plugin is called on a jQuery object containing multiple elements, a separate plugin instance will be created for each element, and each instance will have its own this.element. The second property, this.options, is a hash containing key/value pairs for all of our plugin’s options. These options can be passed to our plugin as shown here.

Note

In our example we use the nmk namespace. The ui namespace is reserved for official jQuery UI plugins. When building your own plugins, you should create your own namespace. This makes it clear where the plugin came from and whether it is part of a larger collection.

When we call jQuery.widget it extends jQuery by adding a method to jQuery.fn (the same way we'd create a standard plugin). The name of the function it adds is based on the name you pass to jQuery.widget, without the namespace; in our case it will createjQuery.fn.progressbar. The options passed to our plugin get set in this.options inside of our plugin instance. As shown below, we can specify default values for any of our options. When designing your API, you should figure out the most common use case for your plugin so that you can set appropriate default values and make all options truly optional.

Now that we can initialize our progress bar, we’ll add the ability to perform actions by calling methods on our plugin instance. To define a plugin method, we just include the function in the object literal that we pass to jQuery.widget. We can also define “private” methods by prepending an underscore to the function name.

To call a method on a plugin instance, you pass the name of the method to the jQuery plugin. If you are calling a method that accepts parameters, you simply pass those parameters after the method name.

Note

Executing methods by passing the method name to the same jQuery function that was used to initialize the plugin may seem odd. This is done to prevent pollution of the jQuery namespace while maintaining the ability to chain method calls.

One of the methods that is automatically available to our plugin is the option method. The option method allows you to get and set options after initialization. This method works exactly like jQuery’s css and attr methods: you can pass just a name to use it as a setter, a name and value to use it as a single setter, or a hash of name/value pairs to set multiple values. When used as a getter, the plugin will return the current value of the option that corresponds to the name that was passed in. When used as a setter, the plugin’s _setOption method will be called for each option that is being set. We can specify a _setOption method in our plugin to react to option changes.

One of the easiest ways to make your plugin extensible is to add callbacks so users can react when the state of your plugin changes. We can see below how to add a callback to our progress bar to signify when the progress has reached 100%. The _trigger method takes three parameters: the name of the callback, a native event object that initiated the callback, and a hash of data relevant to the event. The callback name is the only required parameter, but the others can be very useful for users who want to implement custom functionality on top of your plugin. For example, if we were building a draggable plugin, we could pass the native mousemove event when triggering a drag callback; this would allow users to react to the drag based on the x/y coordinates provided by the event object.

Callback functions are essentially just additional options, so you can get and set them just like any other option. Whenever a callback is executed, a corresponding event is triggered as well. The event type is determined by concatenating the plugin name and the callback name. The callback and event both receive the same two parameters: an event object and a hash of data relevant to the event, as we’ll see below.

If your plugin has functionality that you want to allow the user to prevent, the best way to support this is by creating cancelable callbacks. Users can cancel a callback, or its associated event, the same way they cancel any native event: by calling event.preventDefault() or using return false. If the user cancels the callback, the _trigger method will return false so you can implement the appropriate functionality within your plugin.

In some cases, it will make sense to allow users to apply and then later unapply your plugin. You can accomplish this via the destroy method. Within the destroy method, you should undo anything your plugin may have done during initialization or later use. The destroy method is automatically called if the element that your plugin instance is tied to is removed from the DOM, so this can be used for garbage collection as well. The default destroy method removes the link between the DOM element and the plugin instance, so it’s important to call the base function from your plugin’sdestroy method.

Please visit http://github.com/rmurphey/jqfundamentals to contribute!

This chapter covers a number of jQuery and JavaScript best practices, in no particular order. Many of the best practices in this chapter are based on the jQuery Anti-Patterns for Performancepresentation by Paul Irish.

Selector optimization is less important than it used to be, as more browser implementdocument.querySelectorAll() and the burden of selection shifts from jQuery to the browser. However, there are still some tips to keep in midn.

When you move beyond adding simple enhancements to your website with jQuery and start developing full-blown client-side applications, you need to consider how to organize your code. In this chapter, we'll take a look at various code organization patterns you can use in your jQuery application and explore the RequireJS dependency management and build system.

Before we jump into code organization patterns, it's important to understand some concepts that are common to all good code organization patterns.

Units of functionality should be loosely coupled — a unit of functionality should be able to exist on its own, and communication between units should be handled via a messaging system such as custom events or pub/sub. Stay away from direct communication between units of functionality whenever possible.

The concept of loose coupling can be especially troublesome to developers making their first foray into complex applications, so be mindful of this as you're getting started.

The first step to code organization is separating pieces of your application into distinct pieces; sometimes, even just this effort is sufficient to lend

An object literal is perhaps the simplest way to encapsulate related code. It doesn't offer any privacy for properties or methods, but it's useful for eliminating anonymous functions from your code, centralizing configuration options, and easing the path to reuse and refactoring.

The object literal above is simply an object assigned to a variable. The object has one property and several methods. All of the properties and methods are public, so any part of your application can see the properties and call methods on the object. While there is an init method, there's nothing requiring that it be called before the object is functional.

How would we apply this pattern to jQuery code? Let's say that we had this code written in the traditional jQuery style:

// clicking on a list item loads some content

// using the list item's ID and hides content

// in sibling list items

$(document).ready(function() {

$('#myFeature li')

.append('<div/>')

.click(function() {

var $this = $(this);

var $div = $this.find('div');

$div.load('foo.php?item=' +

$this.attr('id'),

function() {

$div.show();

$this.siblings()

.find('div').hide();

}

);

});

});

If this were the extent of our application, leaving it as-is would be fine. On the other hand, if this was a piece of a larger application, we'd do well to keep this functionality separate from unrelated functionality. We might also want to move the URL out of the code and into a configuration area. Finally, we might want to break up the chain to make it easier to modify pieces of the functionality later.

The first thing you'll notice is that this approach is obviously far longer than the original — again, if this were the extent of our application, using an object literal would likely be overkill. Assuming it's not the extent of our application, though, we've gained several things:

We've broken our feature up into tiny methods. In the future, if we want to change how content is shown, it's clear where to change it. In the original code, this step is much harder to locate.

We've eliminated the use of anonymous functions.

We've moved configuration options out of the body of the code and put them in a central location.

We've eliminated the constraints of the chain, making the code easier to refactor, remix, and rearrange.

For non-trivial features, object literals are a clear improvement over a long stretch of code stuffed in a $(document).ready() block, as they get us thinking about the pieces of our functionality. However, they aren't a whole lot more advanced than simply having a bunch of function declarations inside of that $(document).ready() block.

The module pattern overcomes some of the limitations of the object literal, offering privacy for variables and functions while exposing a public API if desired.

In the example above, we self-execute an anonymous function that returns an object. Inside of the function, we define some variables. Because the variables are defined inside of the function, we don't have access to them outside of the function unless we put them in the return object. This means that no code outside of the function has access to the privateThing variable or to thechangePrivateThing function. However, sayPrivateThing does have access toprivateThing and changePrivateThing, because both were defined in the same scope assayPrivateThing.

This pattern is powerful because, as you can gather from the variable names, it can give you private variables and functions while exposing a limited API consisting of the returned object's properties and methods.

Below is a revised version of the previous example, showing how we could create the same feature using the module pattern while only exposing one public method of the module,showItemByIndex().

Note

This section is based heavily on the excellent RequireJS documentation athttp://requirejs.org/docs/jquery.html, and is used with the permission of RequireJS author James Burke.

When a project reaches a certain size, managing the script modules for a project starts to get tricky. You need to be sure to sequence the scripts in the right order, and you need to start seriously thinking about combining scripts together into a bundle for deployment, so that only one or a very small number of requests are made to load the scripts. You may also want to load code on the fly, after page load.

RequireJS, a dependency management tool by James Burke, can help you manage the script modules, load them in the right order, and make it easy to combine the scripts later via the RequireJS optimization tool without needing to change your markup. It also gives you an easy way to load scripts after the page has loaded, allowing you to spread out the download size over time.

RequireJS has a module system that lets you define well-scoped modules, but you do not have to follow that system to get the benefits of dependency management and build-time optimizations. Over time, if you start to create more modular code that needs to be reused in a few places, the module format for RequireJS makes it easy to write encapsulated code that can be loaded on the fly. It can grow with you, particularly if you want to incorporate internationalization (i18n) string bundles, to localize your project for different languages, or load some HTML strings and make sure those strings are available before executing code, or even use JSONP services as dependencies.

The easiest way to use RequireJS with jQuery is to download a build of jQuery that has RequireJS built in. This build excludes portions of RequireJS that duplicate jQuery functionality. You may also find it useful to download a sample jQuery project that uses RequireJS.

Using RequireJS in your page is simple: just include the jQuery that has RequireJS built in, then require your application files. The following example assumes that the jQuery build, and your other scripts, are all in a scripts/ directory.

The call to require(["app"]) tells RequireJS to load the scripts/app.js file. RequireJS will load any dependency that is passed to require() without a .js extension from the same directory as require-jquery.js, though this can be configured to behave differently. If you feel more comfortable specifying the whole path, you can also do the following:

<script>require(["scripts/app.js"]);</script>

What is in app.js? Another call to require.js to load all the scripts you need and any init work you want to do for the page. This example app.js script loads two plugins, jquery.alpha.jsand jquery.beta.js (not the names of real plugins, just an example). The plugins should be in the same directory as require-jquery.js:

RequireJS makes it easy to define reusable modules via require.def(). A RequireJS module can have dependencies that can be used to define a module, and a RequireJS module can return a value — an object, a function, whatever — that can then be consumed by yet other modules.

If your module does not have any dependencies, then just specify the name of the module as the first argument to require.def(). The second argument is just an object literal that defines the module's properties. For example:

Example 10.7. Defining a RequireJS module that has no dependencies

require.def("my/simpleshirt",

{

color: "black",

size: "unisize"

}

);This example would be stored in a my/simpleshirt.js file.

If your module has dependencies, you can specify the dependencies as the second argument torequire.def() (as an array) and then pass a function as the third argument. The function will be called to define the module once all dependencies have loaded. The function receives the values returned by the dependencies as its arguments (in the same order they were required in the array), and the function should return an object that defines the module.

In this example, a my/shirt module is created. It depends on my/cart and my/inventory. On disk, the files are structured like this:

my/cart.js my/inventory.js my/shirt.js

The function that defines my/shirt is not called until the my/cart and my/inventorymodules have been loaded, and the function receives the modules as the cart and inventoryarguments. The order of the function arguments must match the order in which the dependencies were required in the dependencies array. The object returned by the function call defines the my/shirt module. Be defining modules in this way, my/shirt does not exist as a global object. Modules that define globals are explicitly discouraged, so multiple versions of a module can exist in a page at a time.

Modules do not have to return objects; any valid return value from a function is allowed.

Only one module should be required per JavaScript file.

Once you incorporate RequireJS for dependency management, your page is set up to be optimized very easily. Download the RequireJS source and place it anywhere you like, preferrably somewhere outside your web development area. For the purposes of this example, the RequireJS source is placed as a sibling to the webapp directory, which contains the HTML page and the scripts directory with all the scripts. Complete directory structure:

requirejs/ (used for the build tools) webapp/app.html webapp/scripts/app.js webapp/scripts/require-jquery.js webapp/scripts/jquery.alpha.js webapp/scripts/jquery.beta.js

Then, in the scripts directory that has require-jquery.js and app.js, create a file called app.build.js with the following contents:

To use the build tool, you need Java 6 installed. Closure Compiler is used for the JavaScript minification step (if optimize: "none" is commented out), and it requires Java 6.

To start the build, go to the webapp/scripts directory, execute the following command:

# non-windows systems ../../requirejs/build/build.sh app.build.js # windows systems ..\..\requirejs\build\build.bat app.build.js

Now, in the webapp-build directory, app.js will have the app.js contents, jquery.alpha.jsand jquery.beta.js inlined. If you then load the app.html file in the webapp-builddirectory, you should not see any network requests for jquery.alpha.js andjquery.beta.js.

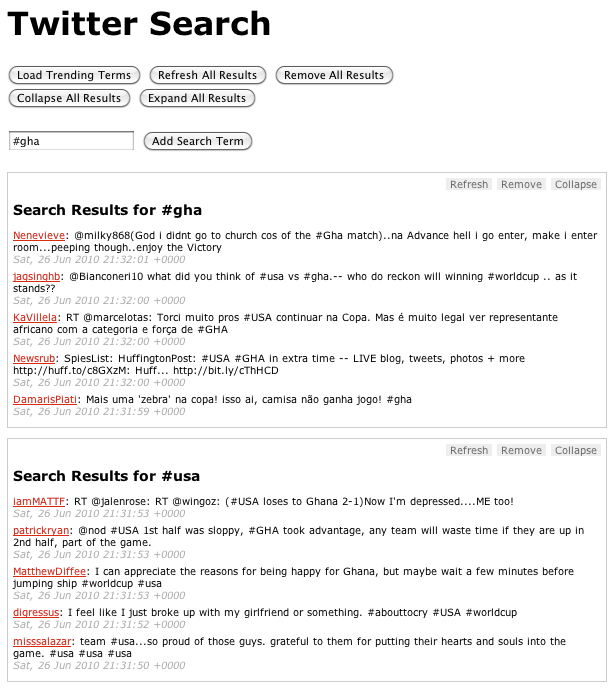

We’re all familiar with the basic events — click, mouseover, focus, blur, submit, etc. — that we can latch on to as a user interacts with the browser. Custom events open up a whole new world of event-driven programming. In this chapter, we’ll use jQuery’s custom events system to make a simple Twitter search application.

It can be difficult at first to understand why you'd want to use custom events, when the built-in events seem to suit your needs just fine. It turns out that custom events offer a whole new way of thinking about event-driven JavaScript. Instead of focusing on the element that triggers an action, custom events put the spotlight on the element being acted upon. This brings a bevy of benefits, including:

Behaviors of the target element can easily be triggered by different elements using the same code.

Behaviors can be triggered across multiple, similar, target elements at once.

Behaviors are more clearly associated with the target element in code, making code easier to read and maintain.